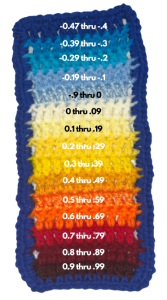

Manatee Painting, acrylic on canvas

The Florida Manatee has been classified as threatened since 2017, when it got downlisted from endangered on the Endangered Species Act. Since this downlisting, thousands of manatees have died. Over a thousand manatees died in 2021 and almost five thousand manatees died in 2022. A large reason for manatee mortality is boat collisions. Manatees often die from getting badly scraped by propellers or by getting hit by the hull of fast-moving boats. Furthermore, water pollution caused seagrass to die in some warm water areas in which manatees gather during the winter, such as Indian River Lagoon. This caused many manatees to starve to death. In 2021 the water pollution worsened to the extent that conservationists dumped over 200,000 pounds of lettuce into the water to feed wild manatees during the winter. Without proper governmental protections, manatee numbers are in risk of declining once again. In this painting, the water around the manatees is devoid of life –– and seagrass. This is meant to symbolize the trouble for manatees if action is not taken soon. Without cleaning up pollution and stopping seagrass from dying, manatees and other marine life could have severe population declines. I hope that manatees can get listed as endangered once again to increase their governmental protections and that the Florida governor will sign bills to clean up the waterways to promote seagrass growth. While strengthening laws to help manatees will take lots of work and collaboration between governments, citizens, and conservationists, it is necessary to save this gentle giant.

Anderson, Curt Anderson. “Lettuce Is on the Menu Again to Help Starving Manatees in Florida.” WFSU News, WFSU, 18 Nov. 2022, https://news.wfsu.org/state-news/2022-11-18/lettuce-is-on-the-menu-again-to-help-starving-manatees-in-florida.

Jones, Robert C. “No Longer Endangered, Manatees Now Face Another Crisis.” University of Miami News and Events, University of Miami, 14 Jan. 2023, https://news.miami.edu/stories/2022/02/no-longer-endangered,-manatees-now-face-another-crisis.html.

https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil

https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil

Artist Statement

Artist Statement