By Charlotte Moore

A few weeks ago, my family and I took a trip to New York City. While we were there, we visited the Guggenheim Museum, where we were lucky to experience the “Countryside, The Future” exhibit that told the stories of rural innovations across the globe. One of these particularly struck me: the Dutch concept of pixel farming. As a member of a peculiar subset of the human family who happens to adore math, I was struck by its attempt to combine Cartesian models with agriculture.

![]() So, what is pixel farming? Simply put, it is a solution to the problems created by agricultural monocultures. When one crop is grown across thousands of neighboring acres, it creates more than a handful of problems. The single crop attracts only a few species of insects, and thus pesticides and insecticides must be used. The crop depletes the soil, and the area’s biodiversity decays rapidly. Cultivating these massive plots contributes to CO2 emissions and both air and water pollution.

So, what is pixel farming? Simply put, it is a solution to the problems created by agricultural monocultures. When one crop is grown across thousands of neighboring acres, it creates more than a handful of problems. The single crop attracts only a few species of insects, and thus pesticides and insecticides must be used. The crop depletes the soil, and the area’s biodiversity decays rapidly. Cultivating these massive plots contributes to CO2 emissions and both air and water pollution.

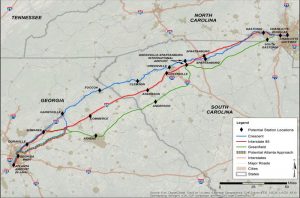

Pixel farming combats all these adverse effects. A pixel farm looks like exactly what it sounds like: a grid of pixels, each representing a different crop. At Campus Almwerk, the world’s first pixel farm, in the Netherlands, the nine-hectare farm is divided into 2 foot-by-2 foot plots. Each plot is planted with a different crop, and its placement in the field is deliberately considered through analysis of other nearby crops and their root systems, soil preferences, and growth patterns. The arrangement of plots is designed to test how the intimate proximity of different crops affects the crops’ interaction and the ecological balance of the farm.

And it has had drastic results. Campus Almwerk has seen an increase in biodiversity and a 50% increase in crop yield. The variety of crops attracts a diverse insect population that eliminates the need for insecticides, reducing the farm’s contribution to water pollution. Planting similar crops apart from one another has also dramatically dampened the spread of disease among crop varieties. All these benefits lead to only one natural conclusion: is this the future of agriculture?

What is even more interesting and revolutionary about Campus Almwerk is its digitization. The plots are planted, weeded, and harvested by an autonomous robot that controls the entire process. Through onboard data analytics, it can adapt plots as needed. Additionally, the robot allows local consumers who have bought a plot to view their crops like a real-time, real-life version of FarmVille.

Although I find pixel farming incredibly fascinating and am interested in seeing how it affects farming going forward, I can’t help but wonder how it is affecting humankind’s relationship with the natural world. On one hand, pixel farming appears to be a return to the sporadic nature of wild plant growth. After all, it is increasing variety and biodiversity and reducing the ecological impact of the farm. However, it also appears to be a meticulous attempt to control nature, to force it to work for humans instead of allowing it to act of its own volition, removing its surprises and spontaneity. Maybe that’s not a bad thing, or maybe it is. I suppose it’s for humanity as a whole to decide. Going forward, how are we going to change our natural world? More importantly, will we allow it to change us?

Engwerda, Jan. “Pixel Farming: ‘Plots’ of 10 by 10 Centimeters.” Future Farming, Future Farming, 3 Feb. 2020.

Koekkoek, Arend. Pixel Farming: Farming in a digital era. July 2018. PowerPoint Presentation.

“Rem Koolhaas and AMO Explore Radical Change in the World’s Nonurban Territories in the Guggenheim Exhibition Countryside, The Future.” Guggenheim Museum, February 2020.

Even more concerning than the additional travel time for your weekend getaway, however, is the impact of this heavy traffic on the environment. With weak (although improving!) public transportation in Greenville County and the surrounding areas, the Upstate suffers from severe automobile dependence. The automobile is simply more convenient for most residents, so Greenville citizens pile into their cars and commute to work, travel across the state, or simply zip a mile or two down the road to the grocery store. This is something I see quite often even on Furman’s campus, where students will hop in their car to go anywhere, even to simply drive to class. Although the car’s reliability may be convenient, it has some major drawbacks, including increased traffic and the obvious CO

Even more concerning than the additional travel time for your weekend getaway, however, is the impact of this heavy traffic on the environment. With weak (although improving!) public transportation in Greenville County and the surrounding areas, the Upstate suffers from severe automobile dependence. The automobile is simply more convenient for most residents, so Greenville citizens pile into their cars and commute to work, travel across the state, or simply zip a mile or two down the road to the grocery store. This is something I see quite often even on Furman’s campus, where students will hop in their car to go anywhere, even to simply drive to class. Although the car’s reliability may be convenient, it has some major drawbacks, including increased traffic and the obvious CO