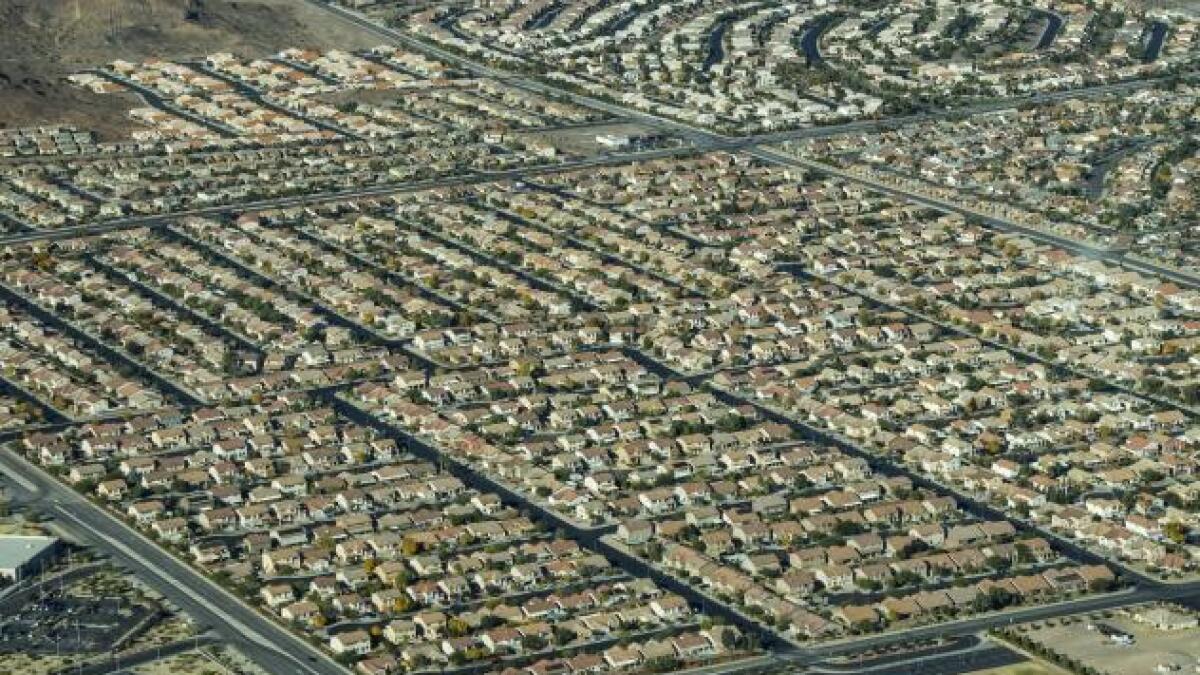

Using explanations from multiple sources, “urban sprawl” is a term used to describe a consequence of poor urban planning, wherein expansion occurs in areas further away from urban centers, encouraging housing development at the edge of urban areas instead of in the urban centers. People are motivated to move to these lower-density suburban areas by the desire for more space, better air quality, reduced noise pollution, lower cost of living, reduced crime rates and the ability to interact more with nature. These all sound like really good reasons to leave urban areas, right? The problem, as pointed out by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), is that these new low-density neighborhoods have a negative impact on environmental, human and economic health (OECD, 2013).

Residents of sprawled communities typically live far from where they work; making them dependent on their own private cars to get to and from work, and to the places they eat and shop. That additional driving results in more air and water pollution, increased greenhouse emissions, and a higher carbon footprint per resident than residents of urban centers produce (OECD, 2013). Because the low-density neighborhoods are often built on rural — and even formerly agricultural — land, urban sprawl also has the tendency to disrupt natural habitats. This disruption not only negatively impacts plant and animal species, it reduces the amount of open land. This development on formerly-open land can create runoff that results in flooding and that can contaminate local water supplies (ASLA, 2016).

Contaminated water and polluted air not only have a negative impact on the health of the environment, these unintended consequences of urban sprawl can have a negative impact on human health as well. There are obvious health consequences like respiratory disease from air pollution and a higher risk of cancer from pollutants in the air in water; but the American Journal of Public Health reports that the more sedentary lifestyle associated with longer commutes can also contribute to the development of cardiac disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Mental health can also be adversely affected by inactivity, considering that residents in areas impacted by urban sprawl might not participate in physical activity that could mitigate the stress and inactivity associated with commuting, since they have less free time (Resnik, 2010). The social consequences of urban sprawl like physical isolation can adversely affect mental health too, because physical isolation and more time spent commuting can result in fewer meaningful relationships to provide social support.

In addition to the environmental and health consequences, urban sprawl can have a negative impact on a community’s economic health. That is because when residents and businesses abandon city centers in favor of less dense areas at the outskirts of a city, money that the local government would spend to maintain and improve existing infrastructure must be divided to provide services like water, electricity, waste services and law enforcement to the outlying areas. An OECD Annual Report points out that service provision for distant and larger service areas is far more expensive than providing those services for a smaller, more compact area, leaving less funding for the urban city center (OECD, 2013). Areas neglected in the city center become less attractive, less valuable, and often less safe. The resulting economic impacts are often disproportionately experienced by people with lower socioeconomic status, who are unable to afford to move from the city center.

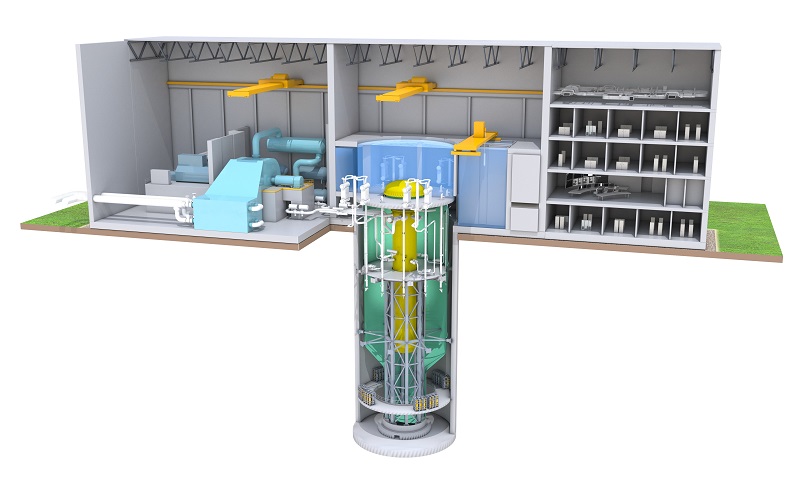

The good news is that there are “smart growth” development strategies that can provide people with more walkable, interconnected, and beautiful areas to live and work in the city center, or within a limited area of the city’s periphery. As suggested in the American Journal of Public Health, these policies encourage living in population-dense areas, but the provision of good sidewalks and biking paths, and attractive green spaces within urban areas can make these urban areas more aesthetically appealing, and encourage people to spend time outdoors, right where they live (Resnik, 2010). Promoting walkability and public transportation helps reduce pollution, thus creating better air and water quality, and healthier lifestyles overall. Dr. David Brody of the Institute for Sustainable Communities recommends strategies like converting abandoned factory buildings to residential buildings to make these urban areas less fragmented and more physically connected to one another, which serves goals of creating efficiency in the provision of infrastructure services as well as maintaining a physical connection between people in the community. Dr. Brody also notes that financial incentives to remain in high-density urban areas can help reduce some of the economic disparities that occur as a result of suburban development (Brody, 2013). Such “smart growth” urban planning policies thus offer a much better alternative to urban sprawl and its environmental, human and economic impacts.

If we make sustainable development our goal, and we are willing to make changes to the current policies that limit sustainable growth, we can reduce urban sprawl and the type of damage that this type of development leaves behind.

Works Cited

ASLA (2017), Smart Policies for a Changing Climate

https://www.asla.org/uploadedFiles/CMS/About__Us/Climate_Blue_Ribbon/climate%20interactive3.pdf

Barrington-Leigh, Christopher, and Adam Millard-Ball. “A century of sprawl in the United States.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 112,27 (2015): 8244-9.

Brody, S. (2013). “The Characteristics, Causes, and Consequences of Sprawling Development Patterns in the United States.” Nature Education Knowledge 4(5):2

Estrada, Francisco, and Pierre Perron. “Disentangling the trend in the warming of urban areas into global and local factors.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences vol. 1504,1 (2021): 230-246.

Euklidiadas, M. Martínez. “Why Is Urban Sprawl Still on the Rise?” Tomorrow.City – The Biggest Platform about Urban Innovation, 19 May 2022, https://tomorrow.city/a/why-is-urban-sprawl-still-on-the-rise.

OECD (2018), “Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

https://www.oecd.org/environment/tools-evaluation/Policy-Highlights-Rethinking-Urban-Sprawl.pdf

Resnik, David B. “Urban Sprawl, Smart Growth, and Deliberative Democracy.” American Journal of Public Health vol. 100, 10 (2010): 1852–1856.

Image Source