By Emma Johnston

As I make my way toward the “Pure in Balance” section in the Dining Hall, I’m magnetically drawn to a tempting beef taco casserole and saucy barbeque meatballs. Then, to my surprise, I look at the menu and realize that they’re made with plant-based meat! When I first saw this at the DH last semester, I was a bit skeptical. Sure, I’d had an Impossible burger before, but could the Furman Dining Hall really pull off cooking plant-based meat at a large scale? I decided I’d give it a try, and as I took my first bite of a meatball, I was pleasantly surprised with its likeness to meat. It had the same texture, smokiness, and overall flavor as an animal-based meatball. Coincidentally, a few days later, my mom sent me a podcast on cell-based meat (also known as “clean” meat), which is a new protein alternative currently in the works. I was infatuated with this idea that meat can be created in a lab using animal cells as a more sustainable, cruelty-free alternative to traditional meat. From that point on, I’ve continued to order the plant-based meat at the DH… and wondered if cell-based meat could become as widespread as plant-based meat, or even plant-based milks.

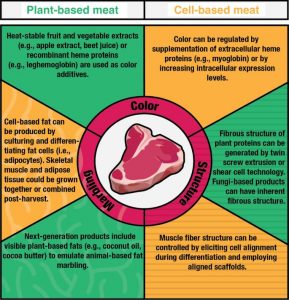

I was still puzzled, and a bit skeptical, about how this “meat clone” could be grown from cells in a lab; it almost sounds like a concept from a sci-fi movie. I learned that cell-based meat is created by producing commodities from muscle or fat cells of animal donors rather than whole organisms. Initial sources of cells are produced by animal donors who are anesthetized while a small section of tissue is removed. In this way, these cells are immortalized and are able to continuously proliferate – in much the same way plants are propagated – so that animal donors don’t have to continue being used. Though plant-based meat (produced from ingredients such as soy, beets, beans, and other grains and vegetables) are already a relatively popular alternative to animal meat, there are notable differences between this iteration and its cell-based sibling. Plant-based meat retains much of the functionality and nutrition of animal protein, but has an altogether different composition than meat, so is less able to mimic flavors and texture. In contrast, cell-based meat is more indistinguishable from traditional meat, as it has been “grown” from the cells of animals and therefore preserves the same composition as animal-based meat (Rubio et al. 2).

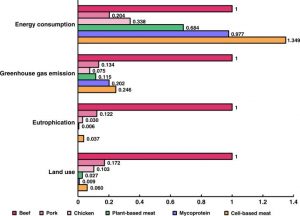

In researching more about cell-based meat, I was amazed to discover its sustainability as an alternative to animal – or even plant-based – meat. Throughout my time at Furman, whether through Eco Reps or a sustainability class, I’ve learned how detrimental animal farming is to the planet, as well as to animal and human health. One of the most destructive aspects of the livestock industry is the amount of greenhouse gas it produces. Methane, a dangerous greenhouse gas with high global warming potential, is produced by livestock – specifically cattle that consume grain-based foods (Garnett et al. 71). The livestock sector is also a major contributor to the production of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that makes up 30% of the ruminant emissions total (Garnett et al. 72). But global warming due to excess greenhouse gas emissions isn’t the only issue linked to animal farming. This industry is responsible for the spread of foodborne illnesses to humans, as well as infectious and zoonotic diseases, like COVID-19. Such pathogens spread through factory farms and meatpacking plants, due to the fact that animals are processed as raw material input for meat production in notoriously unsanitary conditions (Rubio et al. 1). There’s also a conspicuous animal welfare issue within the livestock industry, with billions of animals killed or suffering due to our appetite for animal meat (Rubio et al. 2). However, cell-based meat will eliminate almost all of these issues. According to the journal article “Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production” published by Rubio et al., “The first relevant LCA published in 2011 estimated CBM would involve lower energy consumption (7–45%), greenhouse gas emissions (78–96%), land use (99%), and water use (82–96%) compared to ABM” (Rubio et al. 7). Moreover, with cell-based meat production, it’s almost impossible to spread foodborne illnesses or diseases because cell proliferation requires extremely sterile conditions, preventing contamination of pathogens (Rubio et al. 6). And, since the cells of the animal donors are able to be genetically immortalized, there’s no need for widespread slaughter. Cell-based meat will nearly eliminate the animal suffering, spread of foodborne and zoonotic disease, and most of the environmental issues caused by animal-based meat.

It’s theorized that cell-based meat could reach a larger scale of animal-based meat-eaters than plant-based meat has, since the taste and texture of cell-based meat is extremely similar to that of animal-based meat; there simply wouldn’t be as much for meat-eaters to “give up” in terms of what they enjoy about meat. In fact, studies show that even if cell-based meat was quite a bit more expensive than animal-based meat, there’d still be a relatively large market for it. Recently, a Netherlands consumer acceptance survey was conducted, showing that 58% of interviewees were willing to pay 37% more for cell-based beef compared to animal-based beef (Rubio et al. 3). If this is the case, how close are we to commercializing cell-based meat and producing it at large-scale? Currently, a ramped-up supply of cell-based meat is disrupted by high production costs and a lack of fundamental knowledge on the costs, nutritional value, and sensory properties of these cell-cultured tissues (Rubio et al. 9). Despite these hurdles, there has been some movement toward getting cell-based meat into production. It’s been decided that in the U.S., cell-based meat will be regulated by the FDA, which will regulate cell storage, isolation, and growth, and the USDA, which will oversee these products for the rest of the commercialization process (Rubio et al. 4). In its push for cell-based meat to become a wide scale protein alternative, The Good Food Institute operates as an international nonprofit sharing knowledge and research with the public and working across the supply chain and within public and private sectors to further a mission of promoting alternative proteins. They focus on the science of PBM and CBM, advocate fair policy and public funding to offer solutions to government issues, and find market opportunities and tailored guidance for producing and selling these plant-based and cell-based products (The Good Food Institute). With organizations like GFI and its mobilization of some of the nation’s leading meat producers to reimagine and retool, it’s possible that we could see cell-based protein alternatives being pushed into markets, perhaps becoming as widespread as plant-based meat, in the very near future.

Cell-based meat is a demonstrably sustainable alternative to animal-based meat in that it will decrease environmental, human health, and animal welfare issues. But what is equally exciting is the promise that it could crack open a brand new field requiring the emergence of innovative companies (think meat “breweries”!) and related career opportunities across the world (The Good Food Institute). Cell-based meat may not completely eliminate animal-based meat production. However, the demand for factory-farmed, lower quality meat could be filled by cell-based meat, while animal-based meat made sustainably on a small-scale could become the core of the demand for higher quality meat (Rubio et al. 9). So, rather than wiping out animal-based meat completely, cell-based meat could be offered in tandem with its traditional brethren, satisfying both vegans and carnivores alike.

Sources:

Garnett, Tara, and Cecile Godde. “Grazed and Confused?” Food Climate Research Network, Environmental Change Institute, 2017.

Rubio, N. R., Xiang, N., & Kaplan, D. L. (2020). Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1-11. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20061-y

The Good Food Institute. (2021, February 16). Retrieved March 02, 2021, from https://gfi.org/