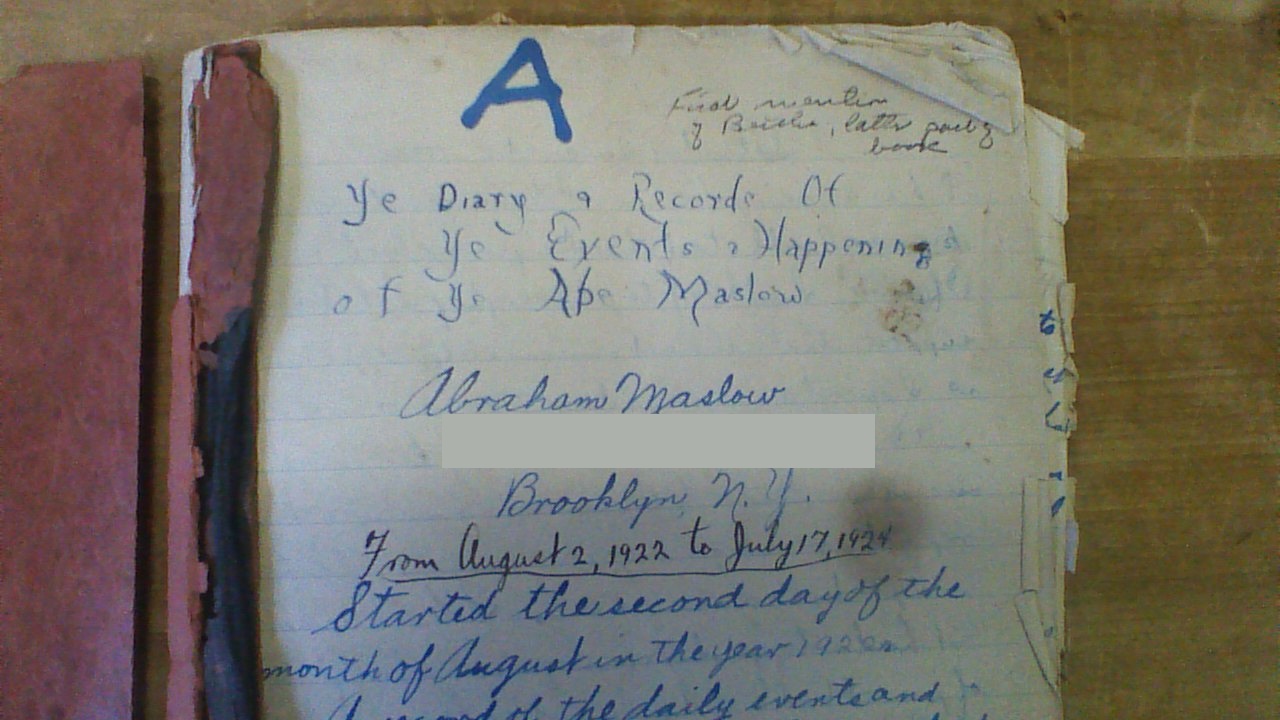

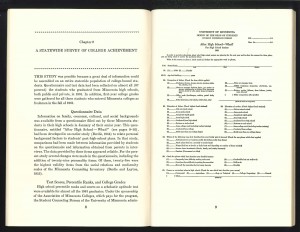

Warning: If read your understanding of human interaction will be forever altered–As of 2012 this book is in its 11th edition!

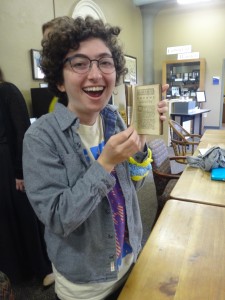

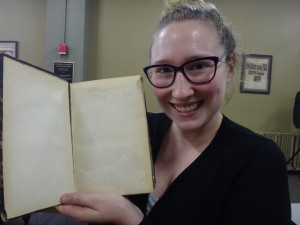

I am fascinated with the work of Elliot Aronson, so I knew that I’d have to find something in the center by him. Luckily, I found The Social Animal, a social psychology textbook he wrote! After perusing the book, I honed in on the chapter on Human Aggression.

Aronson opens this chapter with a personal anecdote. He describes himself nonchalantly explaining to his son that napalm was a weapon that sticks to a victim and “burns him pretty badly.” (Aronson, 1980, p. 159) He then goes on to express his surprise when he looks back at his son and sees him sobbing. This encounter shocked Aronson, and made him wonder if society was becoming desensitized to violence.

Aronson wrote the chapter while “Living in an age of unspeakable horrors –the war in Vietnam, the mass execution of tens of thousands of innocent civilians in Cambodia and Iran, the mass suicide of over 900 people in Jonestown. And yet, although these events are tragic and dramatic, occurrences of this kind are not peculiar to a present decade.” (Aronson, 1980, 160) Aronson is completely right, these horrors are not exclusive to the past, a textbook published in modern times would have a plethora of atrocities to cite.To me, this is the most compelling aspect of Aronson’s book. Even though the world is rapidly evolving before our eyes, human nature is staying virtually constant. Aronson made commentary on a topic that has not been radically changed, and therefore is still relevant today.

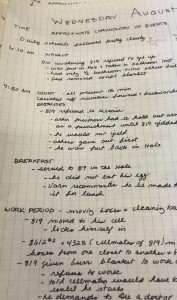

For example, Aronson discusses the environment that sparks riots; a headline we’ve seen all too often in reaction to the Ferguson unrest. Aronson stated that “Aggression can be reduced by eliminating hope–or satisfying it.” He cited an experiment by James Kulik and Roger Brown, in which subjects were asked to make collection calls for charity. A group of the participants were lead to believe that they would have significant success. What Kulik and Brown found was that this group showed significant signs of aggression, such as slamming the phone down, when the confederates repeatedly refused to donate (Aronson, 1980, p. 181). This experiment showed how frustration, or expectation thwarted as Aronson describes it, can create aggression. He notes that the Detroit and Watt (1967, 1965) riots, did not take place in areas of the greatest poverty, rather they took place where there was blatant racial oppression but an opportunity to change the outcome. (Aronson, 1980, p. 183) This is a potential explanation of the riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, the expectation of social justice is what creates the riots, but only because people still have the hope of righting the system.

“Carnage: During the riots in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death, police cars were left abandoned and burned out in the middle of the street while protesters jumped on them” -Posted regarding the Baltimore Riots

The Social Animal is a book that is still very applicable to the current generation; while the world might be a radically different place from 1980, the nature of human aggression is virtually the same. Aronson’s book transcends time because his book is centered around topics that, unfortunately in the case of aggression, remain unchanging.

If only Human Agression was as fluffy and cute as the cartoon introducing the chapter would lead me to believe.

Resources:

Aronson, E. (1980). Human Aggression. In The Social Animal (3rd. ed., pp. 159-193.) San Francisco, California: W.H. Freedman.

Dailymail.com, W. (2015, May 29). Anarchy in Baltimore: Residents claim police have deserted them in wake of Freddie Gray riots as murder rate soars to highest in 15 years, Retreived May 30, 3015. from

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3102433/Anarchy-Baltimore-Streets-turn-bloody-wake-Freddie-Gray-riots-city-sees-homicides-month-15-years-residents-claim-police-deserted-them.html