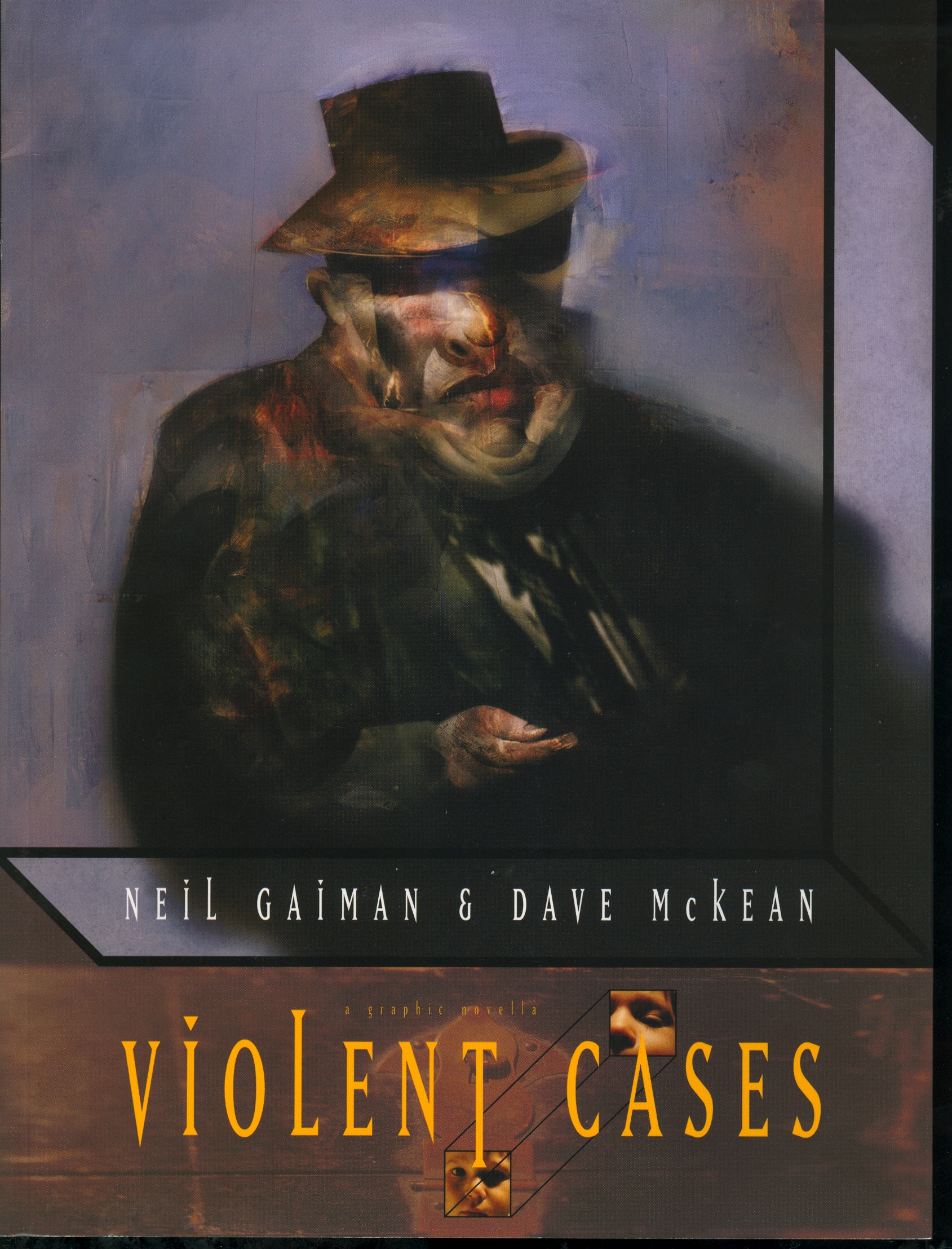

On the dedication page to Dave McKean and Neil Gaiman’s Violent Cases, McKean says, “To my teacher…This is what I mean by comics.” I don’t know the backstory behind this quote, but I can imagine someone, a teacher, telling McKean at some point that comics are for kids, that he was wasting his considerable talent on a medium forever locked to juvenile fantasies about muscle-bound guys in tights. And I imagine, (again, I don’t know any of this) Dave McKean holding up this book or, really, any number of his books, and saying, “Oh yeah? Then check this out.” Maybe it’s so easy for me to conjure up this scene because this is what I have done with his books whenever I’ve encountered somebody who is hesitant about the idea of comics as a real art form. This one is my go-to text, my “converter.”

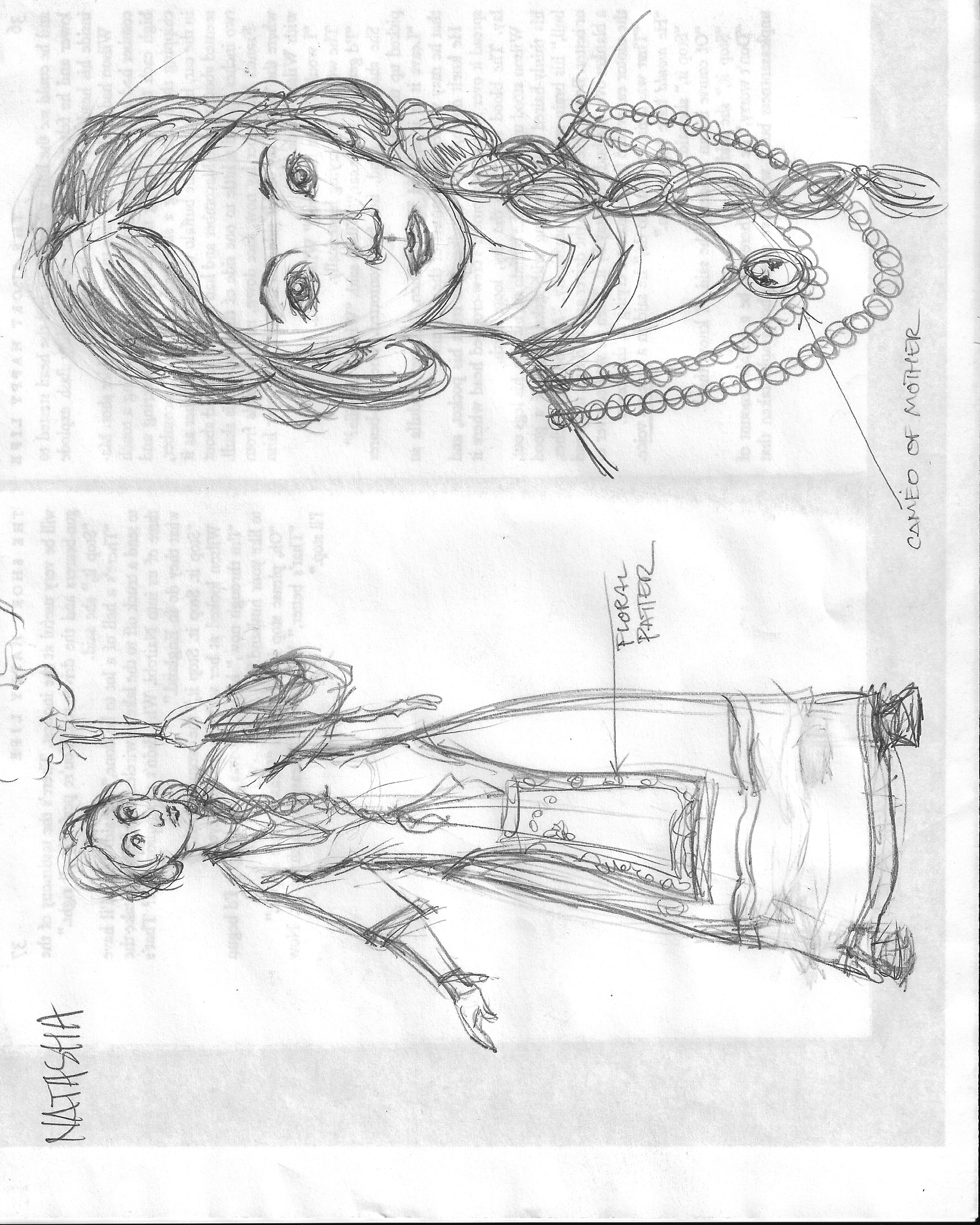

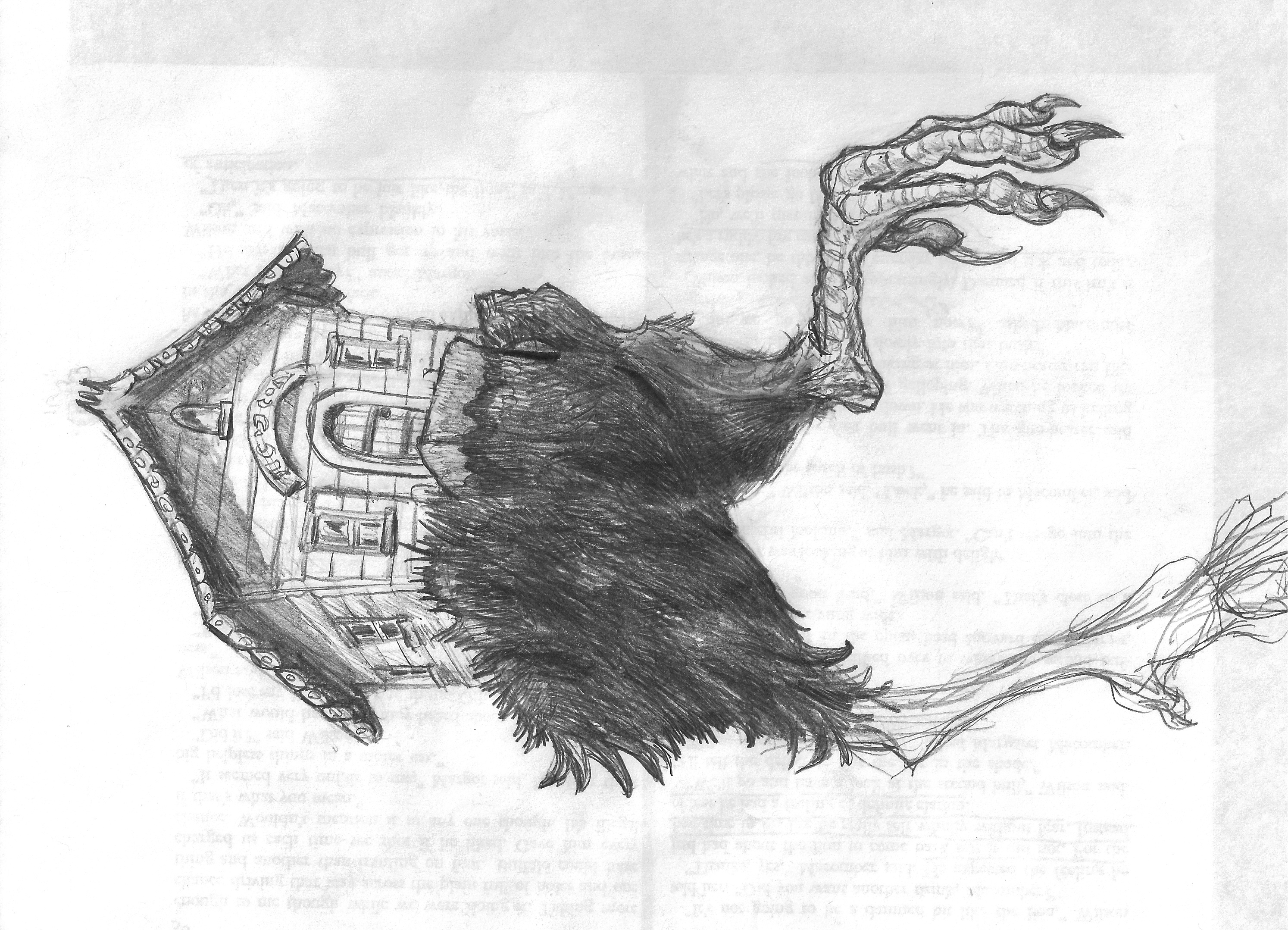

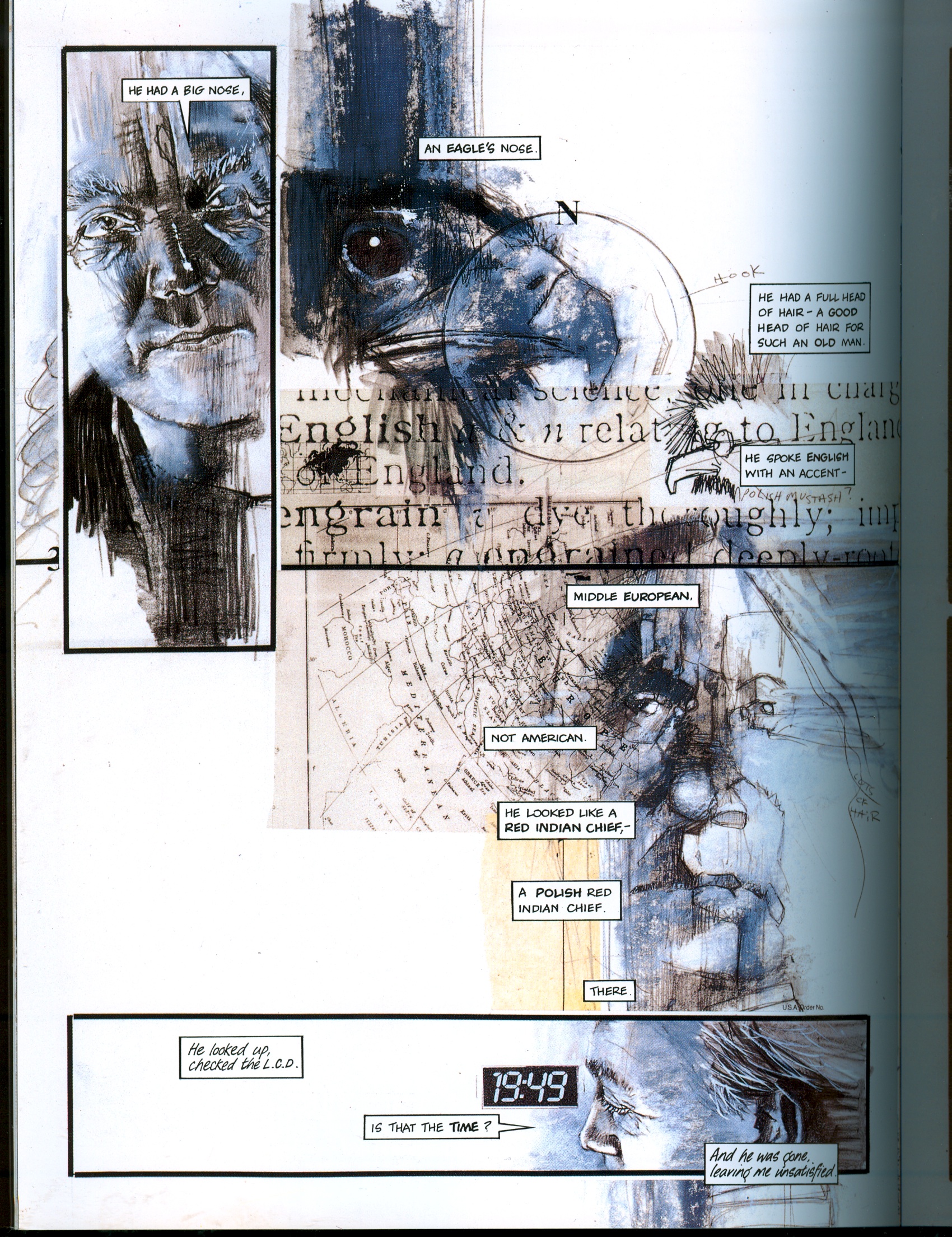

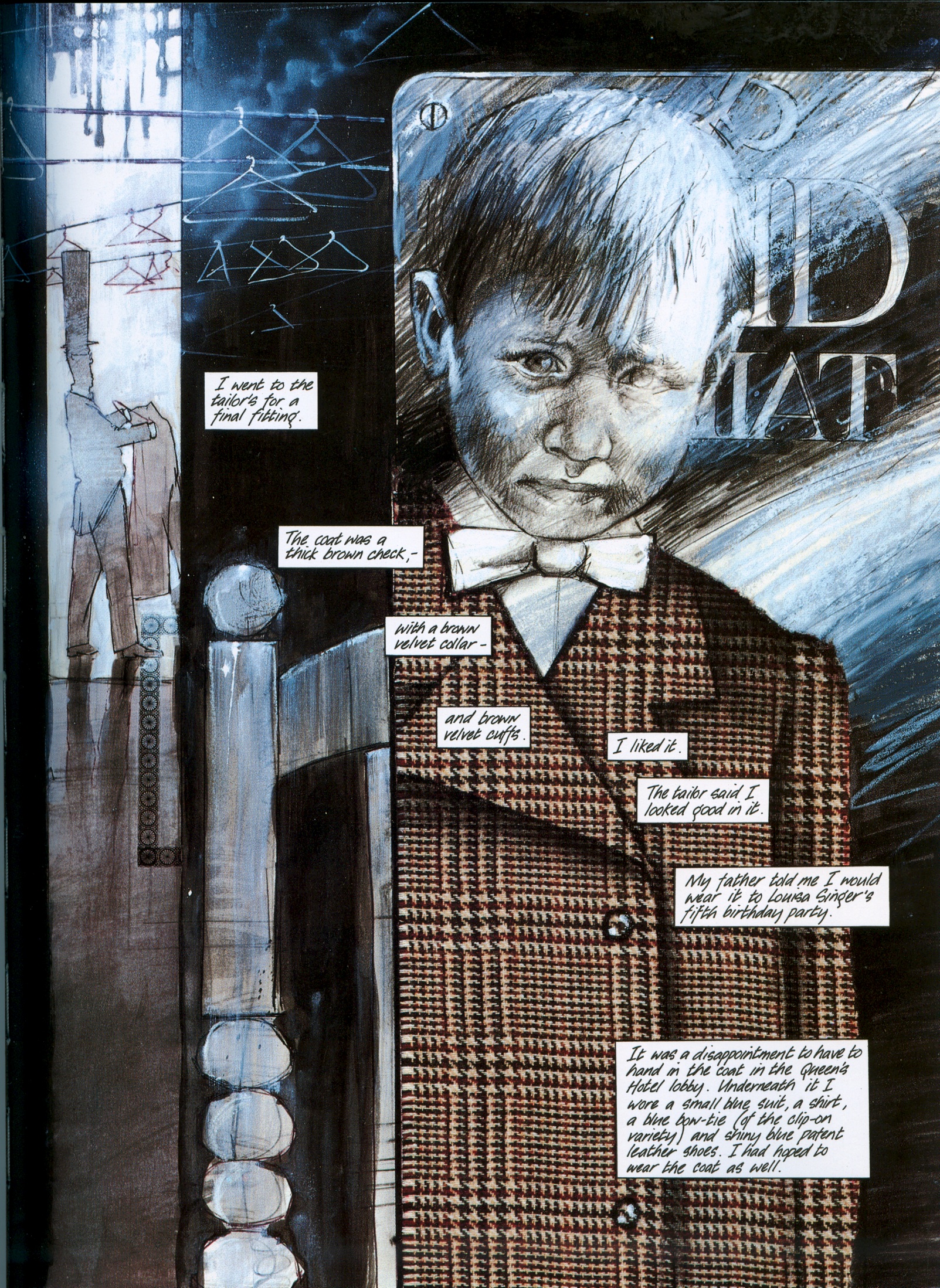

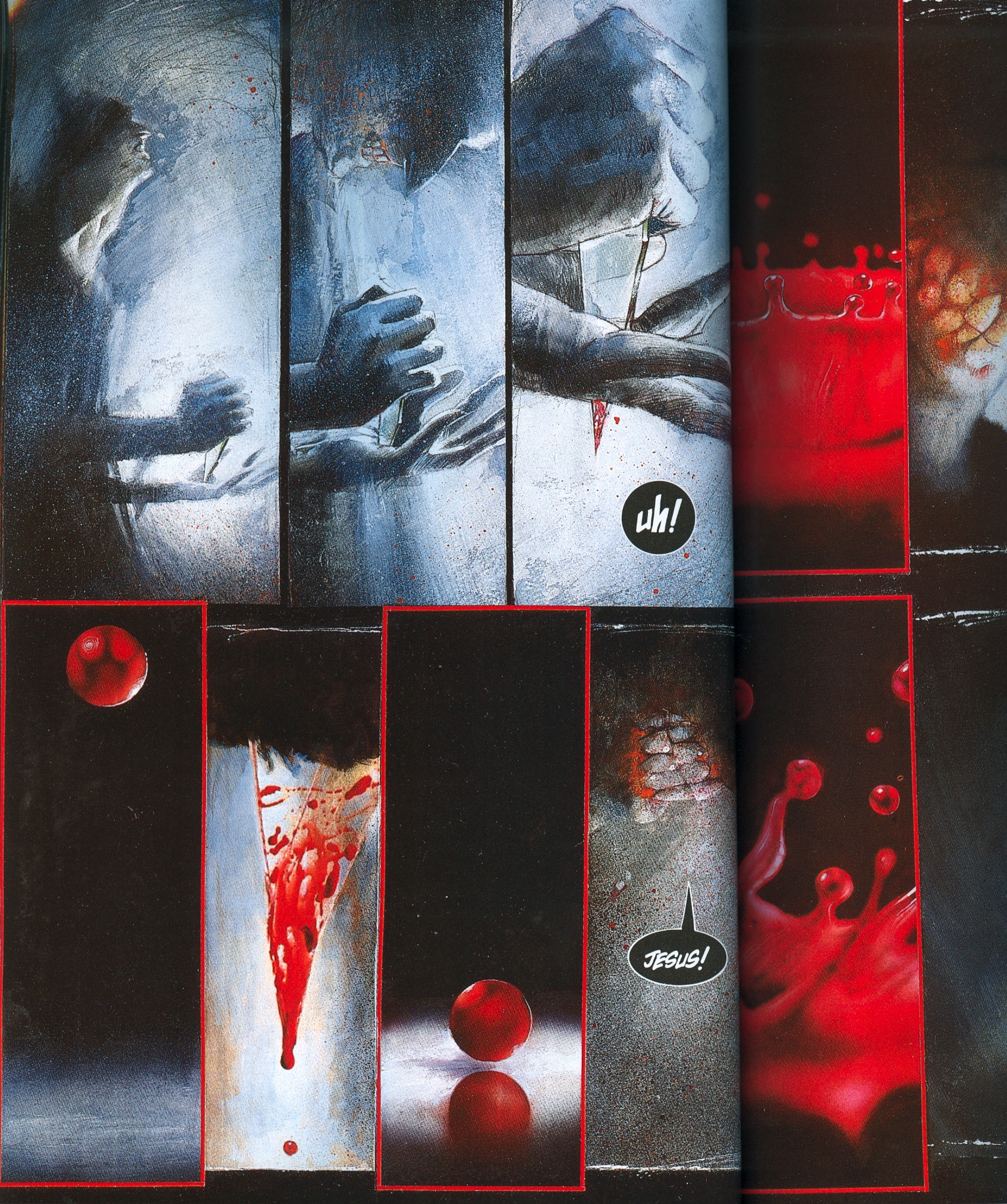

I love so many things about this artist’s work, it’s hard to put it all down. Mostly, it’s the painterly quality, I think. The sense that this is a made thing. Now that may sound silly. Of course it’s a made thing. Art doesn’t just appear or grow in your garden. What I mean is the sense one gets while looking at McKean’s work of the process, the hands behind the image. There are “drawing marks,” scribbles, slashes, places where it seems he has attacked the page with charcoal or color. The fact that some of these images have borders around them, that, taken in all, they support a narrative, does not detract from the individual dynamic qualities of the lines, the gestures, the strokes.

McKean was also the first artist I saw to incorporate what I assume is Photoshop into comic art. Look at the backgrounds of this piece, with the coat hangers, or the photo-quality of the boy’s coat. These, I think, are digitally enhanced photographs coupled with the loose pencil work of the drawing.

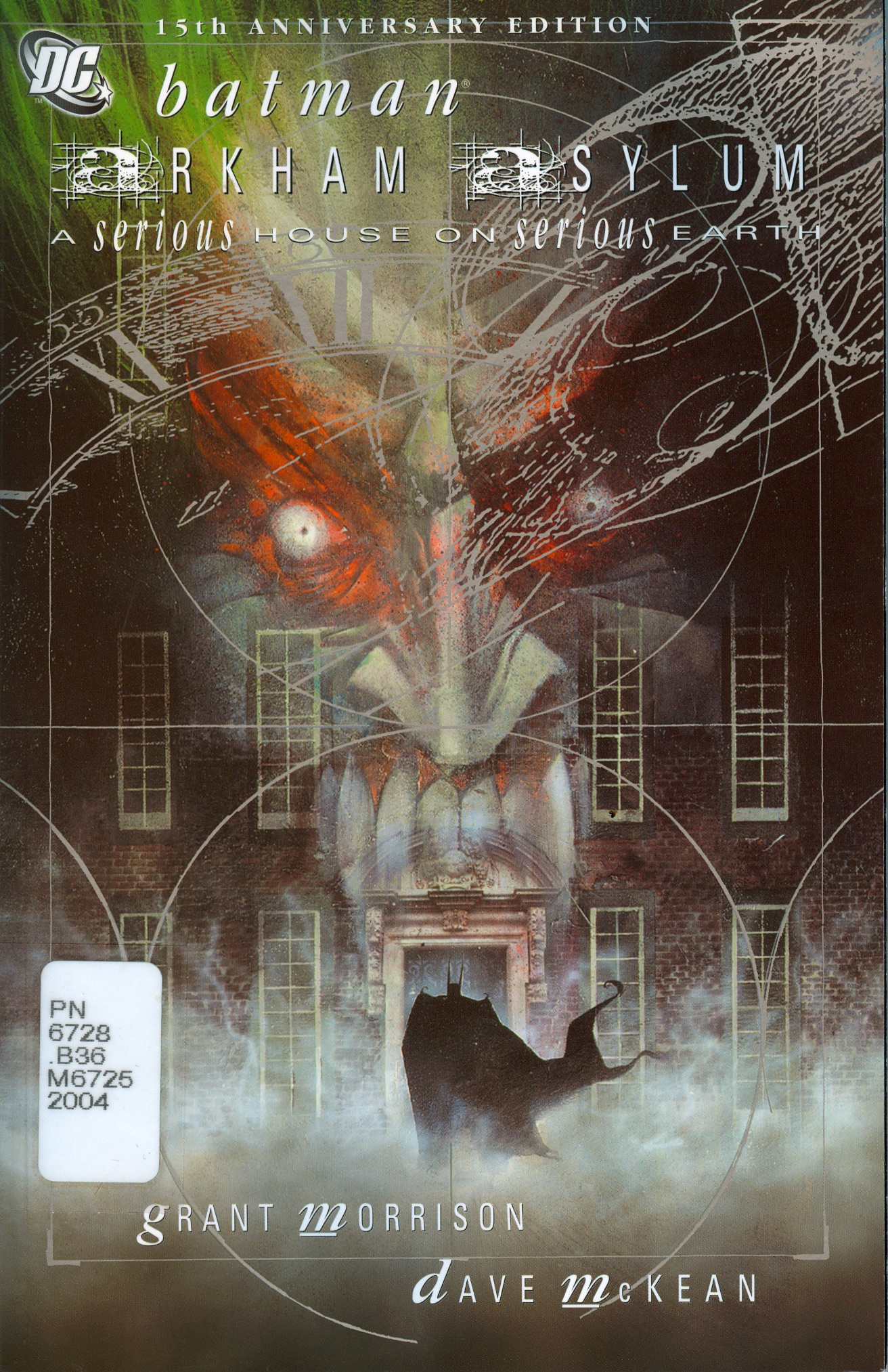

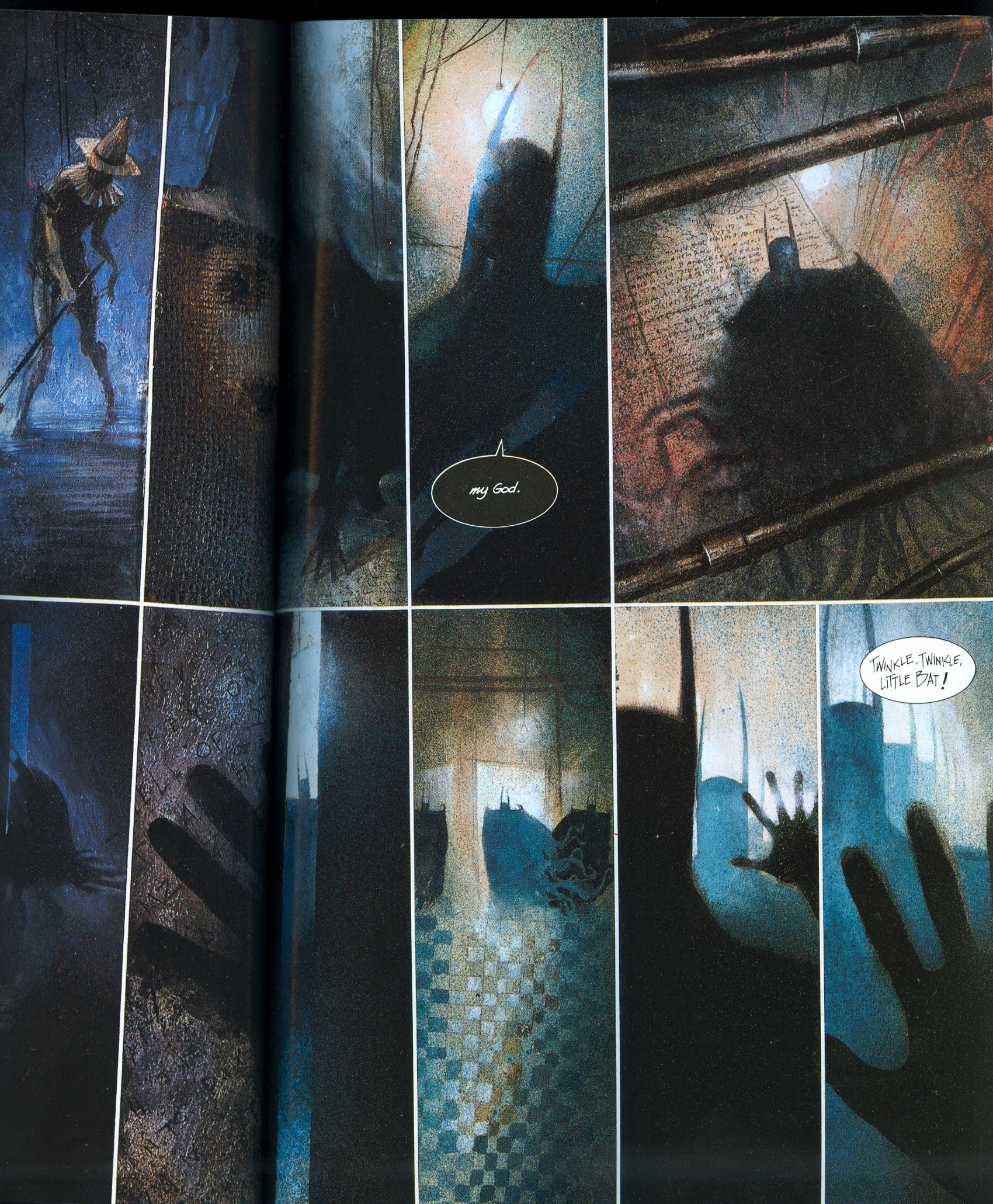

All this is not to say that McKean never draws those musclebound guys. He does, though less frequently, but, my, when he does, he totally reinvents them. In the graphic novel Arkham Asylum, written by Grant Morrison, McKean brings this same painterly style to a traditional superhero story: Batman must descend into the depths of Arkham, the place where all the bad guys he’s nabbed over the years are kept, and there he must do battle with the Joker. Pretty run-of-the-mill stuff as premises go, but the story is actually much better, and the art is incredible.

One way that this is unlike any superhero comic I’ve ever encountered is that you hardly ever get to see the hero. That is, Batman is there, but he’s almost always in shadow, concealed, hidden. Which is perfect, really. Both from a practical level (he’s a guy in dark costume running through shadows, sneaking up on bad guys), and on a symbolic level (this this a test of the character’s soul, a soul that is not all that cheery at the best of times.)

These glimpses of him in shadow, of the iconic silhouette are pretty much all we get, but then again, they’re all we need. Everything else is implied by the atmosphere that the paint and light create.

McKean has done a ton of other work: covers for Gaiman’s Sandman series, illustrations for Gaiman’s kids’ book, fully illustrated children’s book, costume designs for movies, a pack of tarot cards. The body of work is impressive, eery, and, to my mind, inspiring. I hope you enjoy.

Dr. Bernardy