By A. Becklehimer and M. Turner

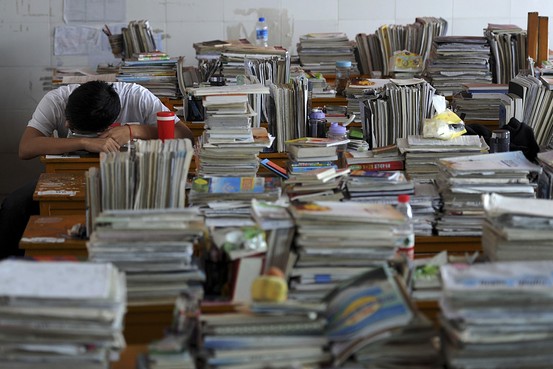

With China’s modern education system clearing not living up to its potential, seen by the only mediocre performance of students and their less than desirable state of health, many people are questioning the problems and how to fix them. Similar in nature to America’s ACT, China’s “Gaokao” test is a cumulative review of their education thus far, and is state mandated (Zhao, Xu, Haste, Selman). Unlike other systems that also take large consideration of other factors, such as personal merit, experience, grades, and involvement, China’s system relies very heavily on this one test, which will forever determine where the student can attend school. The pressure to do well on this test is what has created such a hostile and counterproductive environment to learn in for these students. This pressure is only heightened by the one-child culture China has thrown itself into. As each student is now a second-generation only child, this means they will have two parents and four grandparents that dedicate their time to the child, and will expect highly of the only child to do a good job representing the family. The lack of siblings to divert attention from these students has all the more created an environment that only promotes the drilling of the highly government-regulated education into their minds. Some Chinese parents having tried to take action against this by placing their children in private schools with alternative methods of education, often labeling themselves as havens that will “emphasize the need to help children that develop as individuals.” (Johnson) The goal of these schools is to actually make sure the children leave as smarter and more well rounded individuals, as opposed to the hive-mind the government has attempted to create with state-modified accounts of every little detail.

Ian Johnson. “China’s new bourgeoisie discovers alternative education.” New Yorker Vol. 89, Issue 47 Febuary 3, 2014. 34.

Zhao, Xu, Helen Haste, and Robert L. Selman. “Questionable Lessons From China’s Recent History of Education Reform.” Education Week 33, no. 18 (January 22, 2014): 32.