In late February 2015, the Republican senator from Oklahoma, James Inhofe, brought a snowball from outside the Capitol building onto the Senate floor to prove that the Earth is not getting warmer (Barrett 2015). We can address Inhofe’s misinformation with simple ecological definitions: in which, the climate is the general trend of atmospheric conditions, and the weather is the atmospheric conditions of a discrete moment in time.

Ontology is the branch of philosophy concerned with being. It attempts to answer questions like, “What does it mean for something to be a thing?”; “If you were to break a table in half, do you now have two half-tables or one table that is in two pieces or all three of those things?”; and “How do our interactions with objects change their identities?” With that in mind, Inhofe unintentionally raised a very interesting ontological question that we could frame as, “Without the use of any specific scientific jargon, what is Climate Change?”

Philosopher Sean Esbjorn-Hargens provides one answer, stating, “Climate Change is a complex phenomenon that is enacted by multiple methodologies from various disciplines. No single method by itself can ‘see’ or reveal climate change in its entirety.” He continues, “[Climate Change] is a multiple object. So, while it may be multiple… it is an object nonetheless… it is real!” (Esbjörn-Hargens 2010). So, climate change is a complex web of intersecting and interrelated causes culminating toward a trend. The warming of the Earth is not the only aspect of climate change; it also encompasses poverty, famine, instability, flooding, drought, disease, etc. Climate change’s identity is necessarily entangled with all these factors.

This complexity is very difficult to unravel.

Perhaps this is why much of the up-to-date literature on how we ought to think about climate change, sustainability, and the environment seems to draw an opposite conclusion: mindfulness. Mindfulness, as Ericson et al. write, “[is a meditation practice that] means being aware, taking note of what is going on within ourselves and outside in the world… It can be defined as ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally’… one simply pays attention to one’s experiences, from moment to moment” (Ericson 2014). This doctrine, when applied to the environment, resembles Inhofe’s snowball. Mindfulness seems to suggest that we should care that it’s snowing, not just that it will be warmer next summer.

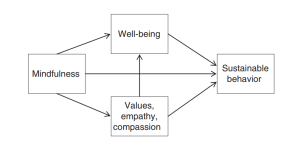

However, research shows that this perspective is useful for developing a more sustainable mindset. “Mindfulness meditation [is] widely practiced for the reduction of stress and promotion of health” (Tang 2015). Additionally, “stress, depression, and physical pain make it harder to consider societal concerns such as climate change” (Ericson 2014). See fig. 1.

This leaves us with a seemingly intractable dilemma—how can we balance the ontological fact of climate change’s complexity and interconnectedness while thinking about it in a way that does not feel completely overwhelming? This can lead to stress and, consequently, more unsustainable behavior.

Tang et al. suggest something akin to what a psychoanalyst might call ego-death. They propose that an ideally mindful practice looks less intrapersonal and more like a breaking down of the walls between the self and the rest of reality. “The distinction between self and object is absent… awareness is itself the subject of awareness” (Tang 2015). On the other hand, Esbjorn-Hargens offers a perspective that claims that the real nature of what climate change is is contingent on your personal relationship with it. “The argument is no longer that methods discover and depict realities. Instead, it is that they participate in the enactment of those realities” (Esbjörn-Hargens 2010).

These arguments are not mutually exclusive, but I don’t think that they are universally applicable. Which I find problematic. Tang’s account is logically consistent but pragmatically unhelpful. Per their own account, years of intentional practice are often necessary before we can measure physical neurological changes from mindfulness (Tang 2015). We must also remember that meditation is hard, achieving ego-death even moreso. Esbjorn-Hargens’ suggestion may fail to resonate with the layperson; if I am not a climatologist, political analyst, or an Arctic researcher, am I really ‘participating in the enactment of reality’? Or, if I am, what else is there to do?

My perspective is that the simple awareness of one’s climate-related stress—or any stress—is as good as it gets. I would still suggest that anyone practice mindfulness; it does help you become happier, healthier, and more sustainable. However, it may not alleviate the overwhelming nature of climate change because it is not designed to do so. As Viktor Frankl once wrote, “An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior” (Frankl 2006). Meditation will not make climate change any less overwhelming; it will only provide you with more freedom in how you experience being overwhelmed. For me, even the simple act of saying to myself, “I am feeling overwhelmed, I am feeling stressed, and the reason is climate change” can provide almost immediate relief.

It’s worth noting that I try to avoid “I am…” and instead start the mantra with “I am feeling…” or “This person is feeling…” in order to create distance between myself and the emotion. When I just state “I am overwhelmed,” that feels like tying up the entirety of my identity with my momentary mental state. This is what separates mindful reflection from Inhofe’s snowball argument. The distinction is between existing in the moment and being tied-up in it. There is a difference between me and the weather, or the climate and my emotions.

References

Barrett T. 2015 Feb 27. Inhofe brings snowball on Senate floor as evidence globe is not warming. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2015/02/26/politics/james-inhofe-snowball-climate-change/index.html.

Ericson T, Kjønstad BG, Barstad A. 2014. Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecological Economics. 104:73–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.007. [accessed 2023 Sep 9]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800914001165.

Esbjörn-Hargens S. 2010. An ontology of climate change integral pluralism and the enactment of multiple objects. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice. 5(1):143–147. [accessed 2023 Sep 9]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283763880_An_ontology_of_climate_change_integral_pluralism_and_the_enactment_of_multiple_objects.

Frankl VE. 2006. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press.Tang Y-Y, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. 2015.

Tang Y-Y, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. 2015. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 16(5):312–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3954.