Esteemed adventurer and hero Chris McCandless wandered into the unforgiving wilderness of Alaska in April of 1992. Ditching all of his personal items and previous life, McCandless died of starvation in August of 1992. His legacy is frequently debated. Some believe him to be an idol: a brave soul who left society behind to find himself. Others believe him to be a fool: an idealistic, naïve man who underestimated the Alaskan wilderness.

My interpretation of Chris is defined by his conclusions of living off the land. Before his death, McCandless wrote “happiness is only real when shared.” (Azevado 2018) After removing himself from society, living off the land, and rejecting help from anyone else, his main take away was that what he was doing was not the answer to his troubled mind. In a day and age where the current generation is constantly being reminded of how troubled our future will be, these words stuck with me.

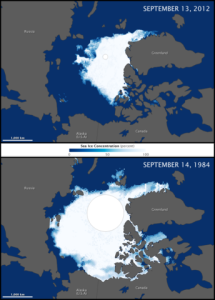

First picture shows difference of 18 years in arctic ice (ABC News), second picture shows the difference of 63 years in Alaska (NASA).

The American Psychology Association (APA) defines eco-anxiety as “the chronic fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the seemingly irrevocable impact of climate change and the associated concern for one’s future and that of next generations.” (APA 2023) My generation is far too familiar with political inactivity, systemic discrimination, and constant environmental degradation. The ignorance of the general public in the face of climate change can be so overwhelming that Chris McCandless’ philosophy of isolation seems enticing.

Although McCandless’ abandonment of civilization was not in light of climate change, it was in light of his resentment of society and the materialistic values of a capitalistic system. Now applying Chris McCandless’ findings to the modern-day context of navigating a world that seems hopeless, we reach the conclusion that the answer is not a hut in the woods. The philosophy of isolationism in this case is selfish and cowardly and the only reason McCandless pursued this life was because—maybe only deep down—he had no intention of returning from the wilderness. What if McCandless lived a life of philanthropy and social connection rather than giving up completely? Would helping and connecting with others not spark introspection and acceptance?

The only way through the problems we will inevitably face, is to tackle them together. After all, humans are, and always have been, social creatures. We must find a way to be less critical and egocentric, and more compassionate and empathetic to those who live their life in constant struggle.

Personally, as an SUS major, my eco-anxiety is lessened by the knowledge that I will always try my best as an individual to address these daunting and seemingly impossible tasks. One in my position must be able to reimagine and question every aspect of our modern-day life. This kind of positive thinking requires a certain fairy-tale, picturesque imagination that can see past the rigid societal structures to envision a world in which children will not have to have to walk miles for drinkable water, violent storms will not shake the foundations of homes, and coastal cities will not be washed away by destructive flooding.

The eco-cabins serve as a bridge between everyday people and habits that must be adopted to create a sustainable future. It has served as a symbol to the Furman community that we acknowledge the lasting effects of climate change and that we will commit ourselves to do everything we can to create a different life in the future. Most importantly, we do it together, as a community, rather than trying to conquer society’s biggest problems solo.

Works Cited:

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). How does climate change affect mental health?. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/climate-change/mental-health-effects