HIDDEN inside the boxes that line the shelves of the Center for the History of Psychology rest artifacts that would drive any developmental psychologist wild. Mary Ainsworth’s letters are neatly filed close to John Bowlby’s infamous video, A Two-Year-Old Goes to Hospital. Copies of nearly every Psychology Today issue are housed a few shelves over. That was where I discovered a 1970 magazine portraying the father of developmental psychology lighting his pipe on the front cover.

Although Jean Piaget would ultimately cultivate a career studying children, his initial schooling focused on biology and philosophy. At the age of ten, Piaget published his first paper: a report on a part-albino sparrow. Around the same time, Piaget studied mollusks at the Natural History in Neuchatel while reading Henri Bergson’s philosophical texts in his spare time.

The Center houses a 1972 copy of Piaget’s book. Piaget admits in the interview, “I have taken epistemology away from philosophy but I have not taken it only for psychology. It belongs in all of the sciences.”

In the Psychology Today interview, Piaget revealed that his unconventional background encouraged his later scientific discoveries because he was able to rely on his biologist instincts to ensure his findings were based on empirical evidence in conjunction with his philosophical intuitions to “sit in [his] office and reason.”

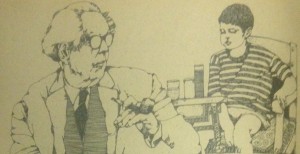

Piaget’s background ultimately served him well as he became a leading figure within psychology. Perhaps his most well-known finding was that children lack an understanding of conservation or the idea that something can change form while maintaining certain qualities (e.g., mass, volume, quantity). Interestingly, Piaget divulged that he initially stumbled across this finding by studying children with epilepsy. In search of a diagnostic test for the condition, he realized these particular children believed Piaget had more coins than beads if three coins comprised a longer line than the four beads did. It wasn’t until Piaget asked neurotypical children the same question that he found that these children, too, did not apply the logic of conservation until around 8 years old. According to Piaget, the novelty of his research was a result of asking children questions that researchers before him found too obvious to ask. Even today, Piaget’s ideas impact the field as researchers continue to identify examples to demonstrate how children conceptualize the world differently than adults.

This cartoon demonstrates one popular version of the conservation task where children compare liquids of the same volume poured into different size containers. (Psychology Today , 1970. Photo by Jennifer Duer)

Piaget concludes the interview by admitting to potential pitfalls of applied psychology. He remarks, “too often psychologists make practical applications before they know what they are applying. We must always keep a place for fundamental research and beware of practical applications when we do not know the foundation of our theories.” As I reflect on my own interests in empirically studying the practical applications of psychology Piaget refers to, I am reminded to keep in mind the biologist’s reliance on evidence, the philosopher’s insistence on reason, and Piaget’s emphasis to merge the two.